Homeopathic Philosophy

Homeopathy is a gentle, deep acting system of medicine that looks at the symptoms of the patient. In the first consultation, a detailed analysis of the presenting complaint symptoms is made through asking varied questions on physical symptoms, medical and family history as well as key characteristics and attributes to build a comprehensive picture of each individual. Some questions may seem unrealistic to the original complaint, but as we treat holistically, every aspect of the individual is relevant. Through specific questioning, the homeopath is able to identify an effective remedy for the patient with a particular complaint. For example, if treating a patient with arthritis, the Homeopath is even interested in the fact that the patients’ feet may be freezing cold at night! The holistic side of homeopathy creates a general sense of well being for the patient, as well as healing for the presenting complaint.

Homeopathy was founded by Dr. Samuel Hahnemann (1755-1843). Based on his observations, Hahnemann published his ideas and experiences in a book called The Organon. The first edition appeared in 1810 and he wrote the last edition (which appeared posthumously) in 1842. As was the custom in those days, he gave numbers to each paragraph in which he explained his different concepts in his poetic style. Each paragraph is called an aphorism.

Here are a four of his famous aphorisms.

Aphorism 2

‘The highest ideal of cure is the rapid, gentle and permanent restoration of health or the removal and annihilation of the disease in its whole extent, in the shortest, most reliable, and most harmless way, on easy comprehensible principles.’

Aphorism 9

In the healthy condition of man, the spiritual vital force (autocracy), the dynamis that animates the material body (organism), rules with unbounded sway, and retains all the parts of the organism in admirable, harmonious, vital operation, as regards both sensations and functions, so that our indwelling, reason-gifted mind can freely employ this living, healthy instrument for the higher purpose of our existence.

Aphorism 17

‘The physician has only to remove the whole of the symptoms in order to annihilate the internal change, the disease itself. When the disease is annulled the health is restored, and this is the highest, the sole aim of the physician who knows the true object of his mission, which consists not in impressive talk, but in giving aid to the sick.’

Aphorism 153

‘In the search for a homoeopathically specific remedy a comparison is made between the collective symptoms of the natural disease and the list of symptoms of known medicines. The symptoms of the case which are chiefly and most solely to be kept in view are those that are the more striking, rare, uncommon and peculiar. The most suitable medicine for effecting the cure is the one where these particular symptoms correspond. The more general and undefined symptoms like loss of appetite, headache, weakness, restless sleep, discomfort and so on, demand little attention, because they are observed in almost every disease and from every drug.’

Just recently I have read the work of Rima Handley in her book ‘ A Homeopathic Love Story – The story of Samuel and Mélanie Hahnemann’ and again was inspired by the stories that surround homeopathy and how this system of medicine originated and evolved into what is used today. So I thought I would include some of the quotes of this book here as quotes, paragraphs and short essays that illustrate the beauty of this medicine and art of homeopathy. How Samuel Hahnemann discovered the first ‘Law of Homeopathy – the treatment of “like with like.” The reception Samuel had from medical doctors and the dedication he showed in discovering an alternative, curative system of medicine. The reasons why Samuel Hahnemann stopped working as a medical doctor and worked solely with chemistry and writing. How Samuel Hahnemann translation work inspired him to take a substance that made him conclude, and became his new system, similia simibilus curentur: “let likes be treated by likes:” How Samuel Hahnemann went public with his opinion for the first time and when he published the word homeopathy for the first time in his “Essay on a New Principle for ascertaining the curative powers of drugs.” The development of two different aspects of homeopathy: the remedy and dosage. The first edition of the Organon explaining the basic principles of homeopathy and the Compassionate side of Samuel Hahnemann. The concept of ‘Provings’ and the first converts to homeopathy and the portrait of Samuel by his second wife Mélanie. To make it easier I have put headings into this section and added in between quotes the picture of the book that all the quotes come from.

‘for homeopathy might be described as a romantic medicine in classical clothing.’ (page 36)

Samuel Hahnemann First ‘Law of Homeopathy the Treatment of “like with like”

‘This reputation came from the medical system he had invented, now called homeopathy, the treatment of “like with like.” Hahnemann had achieved almost magical success by treating sick people with minute amounts of substances capable of causing patterns of illness similar to those from which they were already suffering.’ (page 2)

The Reception Samuel Hahnemann Had From Medical Doctors

‘Samuel Hahnemann had spend the whole of his adult life devoted to medicine, and the last forty years of it had been concentrated intensely on evolving, testing and practising his new system of homeopathy. He had become isolated from society. His direct and forceful nature and his single-minded and uncompromising promotion of his views had made him many enemies, not least among practitioners of orthodox medicine and the apothecaries, the purveyors of its drugs. As can easily be imagined, neither doctors nor apothecaries welcomed the active presence of a man who went about advocating the notion that health was to be regained by giving the smallest possible amount of medicine the smallest amount of times, and who had, almost single-handedly, mounted an unrelenting campaign against all current methods of medical practice.’ (page4)

Samuel Hahnemann Dedication in Discovering an Alternative, Curative System of Medicine.

Hahnemann ‘studied and practised the orthodox medicine of his time, grown disillusioned with it, and bent his considerable energises and mental powers to discovering an alternative, and curative, system if medicine. His whole life had been dedicated o this.’ (page 9)

The Early Years of Samuel Hahnemann that Created Independent Thought

‘It was in these early, difficult days that Samuel seems to have acquitted the habits of self-disciplined study which were so necessary a part of his future achievements. Days of studying on his own at home, and even at school, for he was always far in advance of the other students, provide him with the inclination as well as the capacity for independent thought, a trait which was both to torment and sustain him in the years to come.’ (page 50-51)

Reasons Why Samuel Hahnemann Stopped Working as a Medical Doctor and Worked Solely with Chemistry and Writing

‘A year after settling there (Leipzig) he abandoned medical practise entirely, partly “because it cost ….more than it bought it,” but also because

My sense of duty would not easily allow me to treat the unknown pathological state of my suffering brethren with these unknown medicine … The thought of becoming in this way a murderer or a malefactor towards the life of my fellow human beings was most terrible to me, so terrible and disturbing that I wholly gave up my practise in the first years of my married life … and occupied myself solely with chemistry and writing.’ (page 59)

How Samuel Hahnemann Translation Work Inspired Him To Take A Substance That Made Him Conclude and That Became His New System – similia simibilus curentur: “let likes be treated by likes”

‘Hahnemann was translating the Treatise on Materia Medica of William Cullen, Professor of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh …. when discussing the reasons for the success of what he call Peruvian Bark (the eighteenth century wonder drug cinchona; the bark of cinchona tree, from which quinine was eventually derived) in the treatment of intermittent fever (malaria), Cullen naturally attributed its effectiveness to it “tonic” effect on the stomach. In a foot note which far exceeded the normal brief of a translator, Hahnemann disputed this. He pointed out that the taking of cinchona, or china, produced similar symptoms to these produced by the disease malaria itself and therefore suggested that it was that similarity which was curative and nothing else. Hahnemann gave a detailed account of an experiment he had carried out on himself in which he reproduced the symptoms of malaria by taking systematic overdoses of cinchona:

I took, for several days, as an experiment. four drams of good china twice daily. My feet and finger tips ect., at first became cold; I became languid and drowsy; then my heart began to palpitate; an intolerable anxiety and trembling (but without a rigor); prostration in all the limbs; then pulsation in the head, redness of the cheeks, thirst; briefly, all the symptoms usually associated with intermitted fever appeared in succession, yet without the actual rigor. To sum up: all those symptoms which to me are typical of intermittent fever, a the stupefaction of the senses, a kind of rigidity of all joints, but above all, the numb, disagreeable sensation which seems to have its seat in the periosteum over all the bones of the body – all made their appearances. this paroxysm lasted from two to three hours every time, and recurred when I repeated the dose and not otherwise. I discontinued the medicine and I was once more in good health.

with this thinking Hahnemann had made a significant breakthrough in his thinking. It was to take years to work before he clearly understood the therapeutic application of his perception of the relationship between the symptoms produced by china and the symptoms of intermitted fever; but here, for the first time, he saw the essence of what was to be his new system, similia simibilus curentur: “let likes be treated by likes:” or “Let conditions be treated by thing which are similar.” (page 60 – 61)

How Samuel Hahnemann Went Public With His Opinion For The First Time

‘In 1792 Hahnemann went public with his opinions about venesection when Leopold the second of Austria died suddenly while being treated for a fever, and Hahnemann become involved in the national scandal over the manner of his death:

The bulletins state: ‘On the morning of February 29th, his doctor, Lagusius, found serve fever and a distended abdomen’ – he tried to fight the condition by venesection, and this failed to give relief, he repeated the process three more times, without any better results. We ask, from a scientific point of view, according to what principles has anyone have the right to order a second venesection when the first has failed to bring relief? As for a third, Heaven help us! but to draw blood a fourth time when the three previous attempt failed to alleviate! To abstract the fluid of life four times in twenty-four hours from a man who has lost flesh from mental overwork combined with a long continued diarrhoea, without procuring any relief for him! Science pales before this!’

Hahnemann had declared himself. This is extremely public and contemptuous treatment of the medical handling of the Emperor’s fatal illness caused a sensation. He was no longer an anonymous eccentric; he was an out and out critic of the contemporary medicine. From this point onwards Hahnemann worked with even more fervour then before to developed a new system. (page 61 – 62)

Samuel Hahnemann First Published The Word Homeopathy in his “Essay on a New Principle for Ascertaining the Curative Powers of Drugs.”

‘As Hahnemann and his family moved about Germany, he continued in the most unpropitious circumstances to work passionately towards defining the new system of medicine which he hoped would displace the “old school” he despised. In 1796 he took a decisive step towards this goal in his “Essay on a New Principle for ascertaining the curative powers of drugs, and some clearly articulated the fundamental principle of similia similibus curentur and used his new term “homeopathy”:

One should imitate nature, which, at times, heals a chronic disease by another additional one. One should apply in the disease to be healed, particularly of chronic, that remedy which is able to stimulate another artificially produced disease, as similar as possible; and the former will be head – similia similibus – Likes with Likes”.

Thus 1796 may be regarded as the year in which homeopathy actually began. That year also bought another important medical breakthrough: in England, Dr. Edward Jenner injected a young boy with cow pox and thus demonstrated the principle of vaccination. Hahnemann had in fact already considered this method of treating like with like but had rejected it because of the risks involved in introducing matter derived from disease into the human body. Of course the idea that like could be treated with like was in fact not new at all. The Hippocratic school, medical medicine generally, and Paracelsus quiet specifically, had given ea by guixpression to it in various ways. It had also surfaced more recently in medical writings, for instance those of Antoon de Haen, a pupil of Boerhaave at Leyden, and of the Danish scholar-doctor Georg Stahl, a professor at the University of Halle. What was unprecedented, however, was the sustained consideration of the idea and its systematic application to the treatment of disease, which Hahnemann now began and was to continue working on for the remainder of this long life. He distilled homeopathy from the thought and practise of the past and developed a practical method of applying it by his infinite capacity for taking pains.’ (page 63 -64)

Developing Two Different Aspects of Homeopathy: Remedies and Dosage

‘Much of Hahnemann’s work in these early years of the new century had to do with perfecting his new medicine. In particular he needed to develop two different aspects: the remedies he was to use, and the doses on which he was prescribed them. He and his family spend a lot of time in the countryside, collecting the herbs whose curative properties he wished to establish. Also (because homeopathy uses for more than herbal remedies), Hahnemann the chemist spent long hours in his work room trying to discover methods of releasing the curative properties of metals such as silver and mercury, as well as other substances such as phosphorus. His case books at this early date show that he used mainly remedies such as Belladonna, Chamomilla, Opium, Pulsatilla, Nux Vomica, Veratrum album, Ignatia, Capsicum, Aconite, Ledum and China.’ (page 69)

The First Edition of The Organon Explaining the Basic Principles of Homeopathy

‘The first edition of the Organon is a very clear and simple exposition of what Hahnemann now called Homeopathic medicine. In straightforward terms, Hahnemann explains the basic principles of homeopathy and their application.’ (page 69)

The concept of ‘Provings’

‘Hahnemann gives detailed instructions to how to question a patients in order to elicit the individuality of the disease. This description corresponds very closely to the best advice of other Hippocratic physicians of his time; the physician is to accept the patient’s subjective description of his illness as the best. Once he has established a picture of the symptoms-complex of the disease in the patient by paying careful attention to his description of symptoms, the homeopathic physician must then match this picture to a substance which produced that symptom-complex in a healthy person. Hahnemann states that the effects of remedies should be established by administrating them to healthy people, in control experiments; These test have become to be called “provings” from the German word for “experiment.” Prüfung. He gives details of how to conduct these experiments for provings with various substances and comments that: whenever in the provings of one or other of these medicines, tested in their positive action by observation of the healthy body, we find a symptom-complex analogous to that of a given natural disease, that medicine will, nay, must, be the most suitable counterforce for the destruction and extinction of that natural disorder; the specific, or complete suitable, remedy is discovered in that medicine.’ (page 71)

The Compassionate Side of the Organon

‘Through the pages of this first edition of the Organon, the reader may discern the sort of man that Hahnemann had become: passionate for truth, capable of being tactless to an extraordinarily high degree, and dispose to sweep all aside in his pursuit of the logical of his new system. Above all else, however, the Organon is a work full of compassion. It opens with a clarion call: The physician has the higher aim than to make sick folk well, to pursuit what is called the Art of Healing. The highest ideal of cure is to the speedy, gentle and enduring restoration of health, or the removal and annilation of disease in its entirety, by the quickest, most trustworthy, and least harmful way, according to principles that can readily be understood. (The rational art of healing.)

In later additions he was to follow this up with a rousing paragraph: [The physicians calling] Is not to weave so called systems from fancy ideas and hypotheses about the inner nature of the vital process and the origin of diseases in the invisible interior of the organism (on which so many fame seeking physicians have wasted their powers and time). Nor does it consists of holding forth in unintelligible words or abstract and pompous expressions in an effort to appear learned so as to astonish the ignorant, while the world in sickness cries in vain for help. The tone of the opening of the book gives a good impression of its author, he was a very complex person with an enormous capacity both for feeling and rational thought and a quite incredible capacity for hard work. His philosophical cast of mind, his intellectual bend, was purely a product of the eighteenth century, but his individual striving and his intense pursuit of an individual perception of truth was of the nineteenth. (page 72 – 73)

The First Converts to Homeopathy

‘Nevertheless some students and patients did come to him, and he did find us the support he now sought for the first time. His home became a centre for young converts to homeopathy, a place for Hahnemann at last to relax and unwind in the company of like minded people. Barron von Brunnow wrote afterwards: A very peculiar mode of life prevailed in Hahnemann’s house. the members of his family, the patients and students of the University, lived and moved only in one idea, and that idea was Homeopathy: and for this each strove in his own way. The four grown-up daughters assisted their father in the preparations of his medicines, and gladly took part in the proving … the patients enthusiastically celebrated the effects of homeopathy, and devoted themselves as apostles to spread the fame of the new doctrine among unbelievers. All who adhered to Hahnemann were at that time the butt of ridicule or the objects of hatred. But so much the more did the homoeopathists hold together, like members of a persecuted sect, and hung with more exulted reverence and love upon their honoured head.

Hahnemann was able to relax at home in this supported company, usually in his favourite gaily-figured dressing-gown, the yellow stockings and the black velvet cap. the long pipe was seldom out of his hand and this smoking was the only infraction he allowed himself to commit upon the serve rules of regimen. His drink was water, milk or white beer: and his food of the most frugal sort. The whole of his domestic economy was as simple as his dress and food… After the day had been spend in labour, Hahnemann was in the habit of recruiting himself from eighth to ten o’clock, by conversation which his circle of trusty friends. All his friends and scholars had then access to him, and were made welcome to partake of his Leipsic white beer, and join him in a pipe of tobacco. In the middle of the whispering circle, the old Aesculapius reclined in a comfortable armchair, wrapped in the household dress we have described with a long Turkish pipe in his hand, and narrated, by turns, amusing and serious stories of his storm-tossed life, while the smoke from his pipe diffused its clouds around him.

With the assistance of these friends and collages, Hahnemann was also able to conduct more systematic provings than he had previously been able to do, for he and his students took it upon themselves to experiment with a number of remedies and so add them to the homeopathic armamentarium. Between them they proved numerous substances, including Belladonna, Aconite, Arsenicum, Pulsatilla, and many of the remedies which are the most widely used. (page 75 – 76)

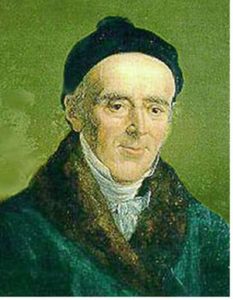

The Portrait of Samuel Hahnemann By His second Wife Mélanie

‘This painting is notable chiefly for its use of deep colours and its portrayal of a Hahnemann who looks very young and happy, almost elf-like. Her portrait captures as aspect of him quiet different form that portrayed in the many representations by other artists which have survived. Most of these, being studies of an “important man,” seem to catch him in a very serious, even sombre mood. His wife’s painting, by contrast, has an almost romantic touch about it and shows the influence of that new mode on Mélanie, even though she had been brought up, trained, and lived her early life in a neo-classic environment.’ (page 34)